Director Damien Chazelle (Whiplash, La La Land) reteams with Ryan Gosling for a dramatic retelling of the story of Neil Armstrong, and NASA’s early efforts to put a man on the Moon. We haven’t been this excited for an astronaut movie since The Right Stuff.

How Special Paint On The Hood Of The World War II Jeep Protected Soldiers’ Lives

If you’ve ever seen a picture of a World War II Jeep with brown paint between the points of its “invasion star,” you might have assumed it was just an aesthetic touch. But it was much more than that: the paint was there to keep soldiers safe. Here’s how.

The paint’s purpose was to protect against chemical weapons attacks. It’s called “M5 liquid vesicant detector paint” (a vesicant is a chemical agent that causes blistering.)

Advertisement

After speaking with avid World War II re-enactor, retired U.S. Marine Corps tank mechanic and connoisseur of WWII Jeep canvases and also vesicant paint (he currently sells replicas of the stuff) Farrell Fox—I learned that this paint was actually standardized by the European Theater of Operations in 1943.

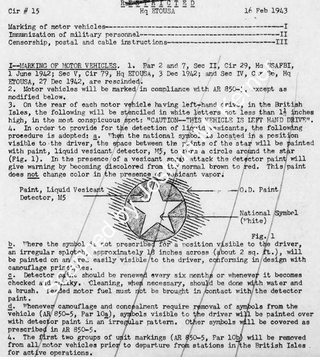

A “restricted” government document, which Fox told me he found in the National Archives, describes how the paint works, and how it should be applied to the five-point star (the star was the “National Symbol of all motor vehicles assigned to tactical units” per the War Department’s 1942 document AR 805-5).

Advertisement

“In order to provide for the detection of liquid vesicants, the following procedure is adopted,” the European Theater of Operations document reads. “When the national symbol is located in a position visible to the driver, the space between the points of the star will be painted with paint, liquid vesicant detector, M5, to form a circle around the star.”

“In the presence of a vesicant spray attack,” the document continues, “the detector paint will give warning by becoming discolored from its normal brown to red,” going on to say that the paint does not work if the vesicant is a vapor.

The document continues, saying that if the star symbol isn’t visible, a two-square foot blotch of paint should be painted on an area that the driver can see, and that the paint has to be renewed twice a year or “whenever it becomes checked and chalky.” The paint should be cleaned with a brush and water, and it should be kept away from leaded fuel, the document states.

It’s no surprise that this paint was meant for the European theater, as Germany had become well-known for its chemical weapons use during World War I.

Advertisement

In fact, according to a paper written by the U.S. Army Soldier and Biological Chemical Command, American researchers during World War I developed a paint out of linseed oil paint and a “du Pont lacquer/linseed oil enamel paint,” copying the Germans, who were painting their mustard shells to detect leaks.

(At the same time, it’s unlikely that the paint actually helped save any lives during the Second World War, as the Nazis are known to have used chemical weapons primarily in concentration camps, and not battlefields. Still, given the extensive use of gas during the previous war by the Germans, it makes sense that it would have been seen as a necessary and practical precaution.)

According to the document, the prototype paint turned from yellow to red within four seconds of contacting a mustard agent, but the research was never finished.

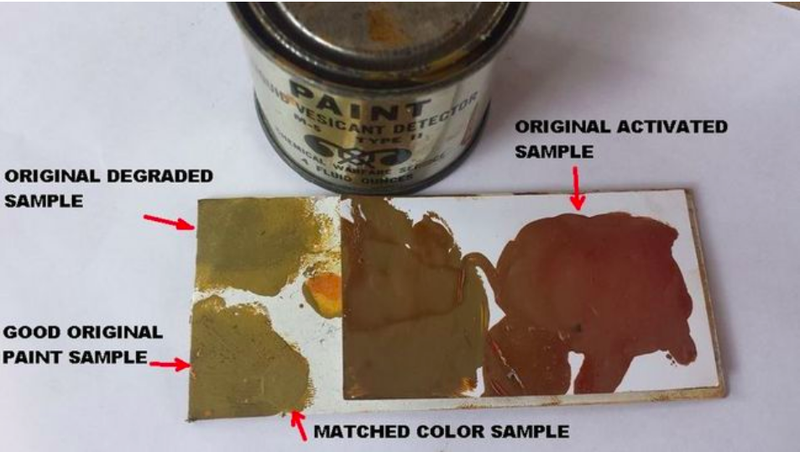

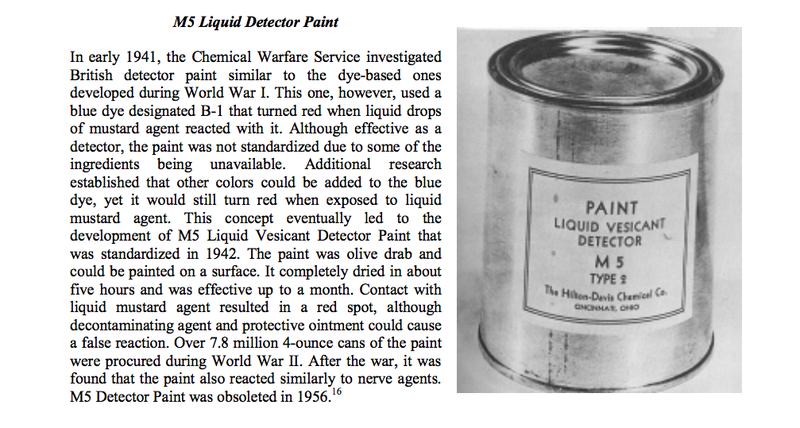

The report goes on, saying that after looking at blue British detector paint in the early 1940s, the U.S. army came up with olive drab M5 Liquid Vesicant Detector Paint (it’s worth noting that a number of sources say the paint was more of a yellowish-brown color), with 7.8 million four-ounce cans making their way to the U.S. military by the end of World War II (here’s one original can for sale on Ebay).

Advertisement

The paint was brushed onto various surfaces, and dried within five hours. After that, for the next month, the paint would turn red when met with a liquid mustard agent. (Note that this conflicts with the European Theater document, which says the detector paint generally works for six months).

Some sources online state that the paint is effective at detecting not just mustard gas (which, it’s worth noting, isn’t actually dispersed as a gas but rather as liquid droplets), but also Lewisite vesicant and even nerve agents.

Using paint to detect such chemicals is crucial, as—according to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons—agents like mustard gas, which have a characteristic odor, tend to dull a victim’s sense of smell “after only a few breaths so that the smell can no longer be distinguished.” In addition, the implementing body of the Chemical Weapons Convention states, respiratory damage can occur in the presence of even tiny, unsmellable concentrations of the agent.

So the paint is there to provide soldiers with a detection method other than smell, which is important, because the effects of mustard gas are devastating, with Lifehacker describing them in an article, writing:

Once exposed, victims smell an odor similar to mustard plants, garlic, or horseradish. Soon, they begin to feel intense itching and skin irritation over the next 24 hours. Gradually, those irritated areas become a chemical burn and victims develop blisters filled with a yellow fluid (here’s the least graphic photo I could find). These burns can range anywhere from first-degree burns to deadly third-degree burns. If one’s eyes are exposed during an attack, blindness is also a possibility.

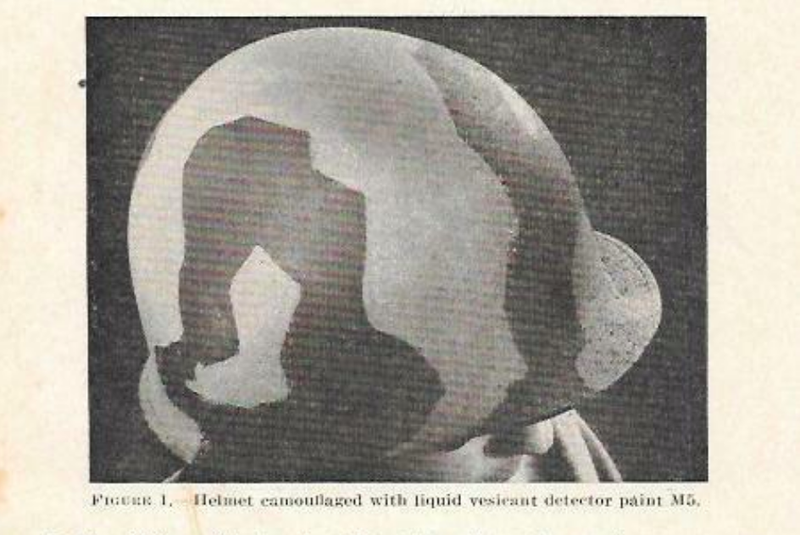

It’s obviously critical for soldiers to be able to recognize the presence of this nasty stuff, which is why the U.S. military used this M5 vesicant detection paint not just on vehicles (more than just Jeeps; thats a Chevy K43 truck hood in the photo above), but also on helmets and on “gas detection brassards,” which Allied soldiers wore on their arms as they invaded Normandy.

via Gizmodo

How Special Paint On The Hood Of The World War II Jeep Protected Soldiers’ Lives

Best Everday Pouch Organizers

So now that you’ve got all the knives, multitools, flashlights, and other accessories, you need a place to keep them at the ready. Everyday Carry shares eight of their picks for great pouches you can use to house and organize all of your small EDC tools.

Our Favorite 4K Monitor Has Never Been Cheaper

Dell’s P2715Q 4K monitor has always been one of the most affordable 27” 4K IPS display on the market, but today, it’s all the way down to $364, the best price we’ve ever seen.

If you aren’t familiar, IPS displays boast superior color accuracy and viewing angles compared to the TN panels you’ll find in most inexpensive 4K monitors. I own the 24” model of this exact monitor, and I absolutely love it, just make sure your computer is powerful enough to drive it.

via Lifehacker

Our Favorite 4K Monitor Has Never Been Cheaper

This Footage of Kilauea Lava Pouring Into the Ocean Is Completely Bananas

It’s been well over a month since the Kilauea volcano on Hawaii’s Big Island started erupting, and molten lava continues to pour into the ocean at a steady pace. New footage shows the dramatic extent to which the lava is producing “laze”—an unholy and potentially deadly mixture of steam, toxic gas, and tiny shards of volcanic glass.

The US Geological Survey captured the stunning video just after 6:00 am local time on June 4, and again in the early afternoon. The wall of laze along the front of the flow is about a half-mile wide.

By the time the morning segment of the video was taken, lava from Fissure 8 had been pouring into the ocean for at least seven hours straight. As it cools, the molten material is forming an entirely new delta in Kapoho Bay. By the time of the afternoon footage, lava had practically filled the shallow bay. This volcano is literally changing the shape of the island before our very eyes.

Advertisement

The laze, a portmanteau of “lava” and “haze,” may look beautiful, but it’s potentially deadly. When the 2,140-degree-Fahrenheit lava hits the ocean, a chemical reaction occurs, producing a mix of hydrochloric acid, steam, and tiny particles of glass. The ensuing clouds of laze can cause lung damage, eye and skin irritation, and death in some extreme cases.

In case you’re wondering, the residents of the homes behind the creeping wall of noxious gas have fled. To date, over 2,500 people have had to evacuate, and more than 300 people are currently seeking refuge at community centers.

[USGS]

via Gizmodo

This Footage of Kilauea Lava Pouring Into the Ocean Is Completely Bananas

Comic for June 05, 2018

Transcript

Dilbert: I told our boss his presentation had a low signal-to-noise ratio and he thought it was a compliment. Wally: I think you just invented my new favorite game. Working for you is like boiling an ocean. Boss: Thank you!

Darrel

A chameleon spies his crush while waiting for the subway, and aims to impress her with a gift. But Darrel doesn’t exactly have the best of luck in this amusing and award-winning animated short film out of Spain, directed by Marc Briones and Alan Carabantes.

More Awesome Stuff:

Highlights From Former Rep. Chris Cox’s Amicus Brief Explaining The History And Policy Behind Section 230

The Copia Institute was not the only party to file an amicus brief in support of Airbnb and Homeaway’s Ninth Circuit appeal of a district court decision denying them Section 230 protection. For instance, a number of Internet platforms, including those like Glassdoor, which hosts specialized user expression, and those like eBay, which hosts transactional user expression, filed one pointing out how a ruling denying Airbnb and Homeaway would effectively deny it to far more platforms hosting far more kinds of user speech than just those platforms behind the instant appeal.

And then there was this brief, submitted on behalf of former Congressman Chris Cox, who, with then-Representative Ron Wyden, had been instrumental in getting Section 230 on the books in the first place. With this brief the Court does not need to guess whether Congress intended for Section 230 to apply to platforms like Airbnb and Homeaway; the statute’s author confirms that it did, and why.

In giving insight into the statutory history of Section 230 the brief addresses the two main issues raised by the Airbnb appeal – issues that are continuing to come up over and over again in Section 230-related litigation in state and federal courts all over the country: does Section 230 apply to platforms intermediating transactional user expression, and does Section 230’s pre-emption language preclude efforts by state and local authorities to hold these platforms liable for intermediating the consummation of the transactional speech. Cox’s brief describes how Congress intended both these questions to be answered in the affirmative and thus may be relevant to these other cases. With that in mind, we are archiving – and summarizing – the brief here.

To illustrate why Section 230 should apply in these situations, first the brief explains the historical context that prompted the statute in the first place:

In 1995, on a flight from California to Washington, DC during a regular session of Congress, Representative Cox read a Wall Street Journal article about a New York Superior Court case that troubled him deeply. The case involved a bulletin board post on the Prodigy web service by an unknown user. The post said disparaging things about an investment bank. The bank filed suit for libel but couldn’t locate the individual who wrote the post. So instead, the bank sought damages from Prodigy, the site that hosted the bulletin board.

[page 3]

The Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy decision alarmed Cox for several reasons. One, it represented a worrying change in judicial attitudes towards third party liability:

Up until then, the courts had not permitted such claims for third party liability. In 1991, a federal district court in New York held that CompuServe was not liable in circumstances like the Prodigy case. The court reasoned that CompuServe “ha[d] no opportunity to review [the] contents” of the publication at issue before it was uploaded “into CompuServe’s computer banks,” and therefore was not subject to publisher liability for the third party content."

[page 3-4]

It had also resulted in a damage award of $200 million dollars against Prodigy. [page 4]. Damage awards like these can wipe technologies off the map. If platforms had to fear the crippling effect that even one such award, arising from just one user, could have on their developing online services, it would dissuade them from being platforms at all. As the brief observes:

The accretion of burdens would be especially harmful to smaller websites. Future startups, facing massive exposure to potential liability if they do not monitor user content and take responsibility for third parties’ legal compliance, would encounter significant obstacles to capital formation. Not unreasonably, some might abjure any business model reliant on third-party content. [page 26]

Then there was also a third, related concern: according to the logic of Stratton Oakmont, which had distinguished itself from the earlier Cubby v. Compuserve case, unlike Compuserve, Prodigy had "sought to impose general rules of civility on its message boards and in its forums." [page 4].

The perverse incentive this case established was clear: Internet platforms should avoid even modest efforts to police their sites. [page 4]

The essential math was stark: Congress was worried about what was going on the Internet. It wanted platforms to be an ally in policing it. But without protection for platforms, they wouldn’t be. They couldn’t be. So Cox joined with Senator Wyden to craft a bill that would trump the Stratton Oakmont holding. The result was the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act, H.R. 1978, 104 Cong. (1995), which, by a 420-4 vote reflecting significant bipartisan support, became an amendment to the Communications Decency Act – Congress’s attempt to address the less desirable material on the Internet – which then came into force as part of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. [page 5-6]. The Supreme Court later gutted the indecency provisions of the CDA in Reno v. ACLU, but the parts of the CDA at Section 230 have stood the test of time. [page 6 note 2].

The statutory language provided necessary relief to platforms in two important ways. First, it included a "Good Samaritan" provision, meaning that "[i]f an Internet platform does review some of the content and restricts it because it is obscene or otherwise objectionable, then the platform does not thereby assume a duty to monitor all content." [page 6]. Because keeping platforms from having to monitor was the critical purpose of the statute:

All of the unique benefits the Internet provides are dependent upon platforms being able to facilitate communication among vast numbers of people without being required to review those communications individually. [page 12]

The concerns were practical. As other members of Congress noted at the time, "There is no way that any of that any of those entities, like Prodigy, can take the responsibility [for all of the] information that is going to be coming in to them from all manner of sources.” [page 14]

While the volume of users [back when Section 230 was passed] was only in the millions, not the billions as today, it was evident to almost every user of the Web even then that no group of human beings would ever be able to keep pace with the growth of user-generated content on the Web. For the Internet to function to its potential, Internet platforms could not be expected to monitor content created by website users. [page 2]

Thus Section 230 established a new rule expressly designed to spare platforms from having to attempt this impossible task in order to survive:

The rule established in the bill […] was crystal clear: the law will recognize that it would be unreasonable to require Internet platforms to monitor content created by website users. Correlatively, the law will impose full responsibility on the website users to comply with all laws, both civil and criminal, in connection with their user-generated content. [But i]t will not shift that responsibility to Internet platforms, because doing so would directly interfere with the essential functioning of the Internet. [page 5]

That concern for the essential functioning of the Internet also explains why Section 230 was not drawn narrowly. If Congress had only been interested in protecting platforms from liability for potentially defamatory speech (as was at issue in the Stratton Oakmont case) it could have written a law that only accomplished that end. But Section 230’s language was purposefully more expansive. If it were not more expansive, while platforms would not have to monitor all the content it intermediated for defamation, they would still have to monitor it for everything else, and thus nothing would have been accomplished with this law:

The inevitable consequence of attaching platform liability to user-generated content is to force intermediaries to monitor everything posted on their sites. Congress understood that liability-driven monitoring would slow traffic on the Internet, discourage the development of Internet platforms based on third party content, and chill third-party speech as intermediaries attempt to avoid liability. Congress enacted Section 230 because the requirement to monitor and review user-generated content would degrade the vibrant online forum for speech and for e-commerce that Congress wished to embrace. [page 15]

Which returns to why Section 230 was intended to apply to transactional platforms. Congress didn’t want to be selective about which types of platforms could benefit from liability protection. It wanted them all to:

[T]he very purpose of Section 230 was to obliterate any legal distinction between the CompuServe model (which lacked the e-commerce features of Prodigy and the then-emergent AOL) and more dynamically interactive platforms. … Congress intended to “promote the continued development of the Internet and other interactive computer services” and “preserve the vibrant and competitive free market” that the Internet had unleashed. Forcing web sites to a Compuserve or Craigslist model would be the antithesis of the congressional purpose to “encourage open, robust, and creative use of the internet” and the continued “development of e-commerce.” Instead, it will slow commerce on the Internet, increase costs for websites and consumers, and restrict the development of platform marketplaces. This is just what Congress hoped to avoid through Section 230. [page 23-24]

And it wanted them all to be protected everywhere because Congress also recognized that they needed to be protected everywhere in order to be protected at all:

A website […] is immediately and uninterruptedly exposed to billions of Internet users in every U.S. jurisdiction and around the planet. This makes Internet commerce uniquely vulnerable to regulatory burdens in thousands of jurisdictions. So too does the fact that the Internet is utterly indifferent to state borders. These characteristics of the Internet, Congress recognized, would subject this quintessentially interstate commerce to a confusing and burdensome patchwork of regulations by thousands of state, county, and municipal jurisdictions, unless federal policy remedied the situation. [page 27]

Congress anticipated that states and local authorities would be tempted to impose liability on platforms, and in doing so interfere with the operation of the Internet by forcing platforms to monitor after all and thus cripple their operation:

Other state, county, and local governments would no doubt find that fining websites for their users’ infractions is more convenient than fining each individual who violates local laws. Given the unlimited geographic range of the Internet, unbounded by state or local jurisdiction, the aggregate burden on an individual web platform would be multiplied exponentially. While one monitoring requirement in one city may seem a tractable compliance burden, myriad similar-but-not-identical regulations could easily damage or shut down Internet platforms. [page 25]

So, "[t]o ensure the quintessentially interstate commerce of the Internet would be governed by a uniform national policy" of sparing platforms the need to monitor, Congress deliberately foreclosed the ability of state and local authorities to interfere with that policy with Section 230’s pre-emption provision. [page 10]. Without this provision, the statute would be useless:

Were every state and municipality free to adopt its own policy concerning when an Internet platform must assume duties in connection with content created by third party users, not only would compliance become oppressive, but the federal policy itself could quickly be undone. [page 13]

This pre-emption did not make the Internet a lawless place, however. Laws governing offline analogs to the services starting to flourish on the web would continue to apply; Section 230 simply prevented platforms from being held derivatively liable for user generated content that violated them. [page 9-10].

Notably, none of what Section 230 proposed was a controversial proposition:

When the bill was debated, no member from either the Republican or Democratic side could be found to speak against it. The debate time was therefore shared between Democratic and Republican supporters of the bill, a highly unusual procedure for significant legislation. [page 11]

It was popular because it advanced Congress’s overall policy to foster the most beneficial content online, and the least detrimental.

Section 230 by its terms applies to legal responsibility of any type, whether under civil or criminal state statutes and municipal ordinances. But the fact that the legislation was included in the CDA, concerned with offenses including criminal pornography, is a measure of how serious Congress was about immunizing Internet platforms from state and local laws. Internet platforms were to be spared responsibility for monitoring third-party content even in these egregious cases.

A bipartisan supermajority of Congress did not support this policy because they wished to give online commerce an advantage over offline businesses. Rather, it is the inherent nature of Internet commerce that caused Congress to choose purposefully to make third parties and not Internet platforms responsible for compliance with laws generally applicable to those third parties. Platform liability for user-generated content would rob the technology of its vast interstate and indeed global capability, which Congress decided to “embrace” and “welcome” not only because of its commercial potential but also “the opportunity for education and political discourse that it offers for all of us.” [page 11-12]

As the brief explains elsewhere, Congress’s legislative instincts appear to have been born out, and the Internet today is replete with valuable services and expression. [page 7-8]. Obviously not everything the Internet offers is necessarily beneficial, but the challenges the Internet’s success pose don’t negate the policy balance Congress struck. Section 230 has enabled those successes, and if we want its commercial and educational benefit to continue to accrue, we need to make sure that the statute’s critical protection remains available to all who depend on it to realize that potential.

Permalink | Comments | Email This Story

via Techdirt

Highlights From Former Rep. Chris Cox’s Amicus Brief Explaining The History And Policy Behind Section 230