How And Why The M16 Failed In Vietnam (And Is It Reliable Today?)

https://ift.tt/3hdDTSx

From VFW halls to online forums, you normally don’t have to go far to find someone proclaiming the evils of the AR-15/M16 and how unreliable it is.

While in recent years these graybeards have been largely drowned out in the flooded market of high-quality AR-15s, there are legitimate reasons behind their criticisms and complaints.

The fact of the matter is, the M16 failed Vietnam warfighters, and Americans died because of it.

How many lost their lives due to the rifle’s early failings? Sadly, we’ll never know—but we do know that the number was not insignificant.

How did this happen? Why did it happen? Who is to blame? And can you trust the AR-15/M16 platform today?

These are all valid questions. Let’s get into it.

Table of Contents

Loading…

Facts From Fiction

Allow me to preface this article with some groundwork: I am not a historian, nor was I alive during the Vietnam war, and, as far as I know, none of my family served in the war either.

I have compiled this information from a number of sources, but the bulk of it comes straight from the Congressional Subcommittee Hearing on the M-16.

Additionally, the declassified Report Of The M16 Rifle Review Panel dated 1 June 1968, and books such as The Black Rifle, Misfire: The Tragic Failure of the M16 in Vietnam, and the Great Rifle Controversy.

To a lesser extent, I also relied on the information provided by Small Arms Solutions.

After hundreds of hours of personal research, I feel confidant providing these details to you. If you’re interested in exploring the nitty-gritty of it all yourself, I encourage you to read the source materials listed above.

The Rifle

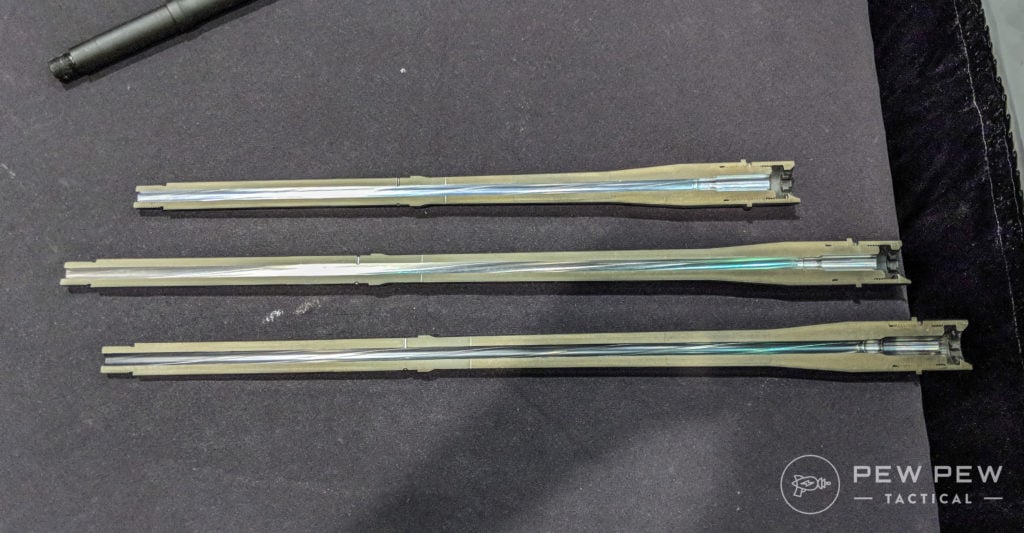

While “M16” is a popular designation for these rifles, the truth is another layer deep. Technically speaking, there were several variations of the M16 in Vietnam.

There were even a few versions that were never given military designations at all. These were sold to the military in small-ish batches under commercial Colt names.

I won’t try to name them here because…well, I’ll probably miss one and get yelled at in the comments.

However, what is important to know is that these rifles worked flawlessly. They were the weapons used by ARVN, the Green Berets, and other “advisers” and special operations units.

The rifles that were mass produced and adopted by the military were, in order of adoption:

- M16

- XM16E1

- M16A1

There are several differences between each of these rifles, but most of them are largely unimportant for the story we’re looking at today.

Simply put, the vast majority of problems were found with the XM16E1.

America’s newest rifle was delivered to the military in 1964, though it wouldn’t face a true trial by fire until the Battle of Ia Drang in 1965.

While the M16 technically shared the same shortcomings as the XM16E1, it was only acquired by the Air Force and in comparatively smaller numbers.

Regulated almost entirely to guard duty, the Air Force’s M16s did not have much opportunity to see combat nor the conditions that resulted in failures.

In some rare cases, the Air Force would continue to use their original M16s until the early 2000s before finally upgrading to the M16A2 pattern.

The M16A1 solved many of the design and manufacturing problems inherent to the M16 family.

Although it was by no means perfect or immune to failure, this version of the M16 was far more reliable than its predecessors, especially in the field.

Unfortunately, the M16A1 would not enter service until 1967.

The Problems

Before we get into the why and who of the matter, let’s examine what went wrong with the XM16E1 in Vietnam.

Early on in the war, the XM16E1 was outstandingly reliable—but I mean VERY early on, as in the first few months.

The Battle of Ia Drang was the first time regular American forces met regular North Vietnamese forces in combat.

Side note, if you haven’t seen We Were Soldiers, you need to.

While the movie doesn’t touch on the matter, the book it was based on explicitly quotes Col. Moore (author) and Sgt. Savage, who both confirmed that their M16s worked flawlessly.

In the book, Col. Moore credits the XM16E1 as being a determining factor in how his unit was able to survive the battle.

Likewise, Sgt. Savage recalls that he “had about thirty magazines in my pack. And no problems with the XM16E1. An hour before dark, three men walked up on the perimeter. I killed all three of them 15 feet away.”

So, how did the XM16E1 go from that to being an unreliable piece of shi-…junk?

Failure To Extract

By far, the most common problem the XM16E1 faced was a failure to extract. After firing, the bolt would unlock and retract, but fail to remove the spent cartridge from the chamber.

Most often, the extractor on the bolt would simply slip off the rim of the spent cartridge.

If you’re lucky, this causes the bolt to short stroke, resulting in a failure to strip a new cartridge from the magazine.

Clearing this malfunction is fairly easy: Drop the magazine, rack the charging handle a bit, and 9 times out of 10 the spent case will come out.

But if you’re unlucky, this could result in a “double-feed.”

This term means that the bolt traveled far enough back to strip a new cartridge from the magazine, but because the chamber is still occupied, the two rounds double-feed.

It’s not the end of the world and can be solved with basically the same fix-it technique, but it is a trickier (and more annoying) scenario.

If you’re really unlucky, the extractor doesn’t slip off the rim of the case and instead rips the rim clean off, leaving the rest of the spent case in the chamber.

This problem can’t be cleared as quickly or easily. You need to drop the magazine, lock the bolt back, pull out your cleaning rod (if you were issued one…), and jam it down the barrel of your rifle to knock the spent case out.

All the while, the enemy is spraying you down with their AK-47s.

Ripped cartridge rims were fairly rare early in the war, but they quickly became a common occurrence.

Bolt Carrier Bounce

Have you ever wondered what exactly your buffer weights do? In part, they prevent bolt carrier bounce.

Bolt carrier bounce is exactly what it sounds like: When the BCG comes forward during the cycle, it strips a new cartridge from the magazine and feeds it into the chamber.

If the BCG is moving too fast, it will chamber the round, lock, and then bounce backward slightly.

This isn’t a big deal if you’re shooting semi-automatic because the BCG will settle forward before you can pull the trigger a second time.

But if the issue occurs during full-auto fire?

Keep in mind that these failed mechanics are occurring within milliseconds of each other. In battle, the difference of a few milliseconds can cost a life.

The U.S. military doctrine of today rarely has the average rifleman employing full-auto in their M16s or M4s. But the doctrine of Vietnam was far more liberal in the use of full-auto—mostly due to ambushes in very dense jungle.

In full-auto, the act of the BCG locking forward is what trips the hammer.

If the BCG trips the hammer but then bounces back slightly while the hammer is coming forward, it prevents the hammer from striking with full force. And often too little force to set off the primer and fire.

It’s the dreaded “click” instead of a “bang”.

The buffer weights are effectively a dead blow hammer inside the rifle and act to keep the bolt from bouncing after it locks in place.

Clearing it is a simple matter of racking the charging handle.

But if you’re spraying full-auto fire to suppress the enemy during an ambush, taking the time to rack a charging handle because your rifle went “click” will leave you with a lifelong bad opinion of the rifle.

If you even survive the ambush.

Slam Fire

If you’ve ever chambered a round in your AR-15 and then removed it without firing, you’ve likely seen a very small dimple on your primer.

That dimple is caused by the free-floating firing pin in the BCG.

How is that safe? Simple, the primer needs a lot more force to set off than what the inerta from the firing pin can provide…. at least today it does.

The M16 and XM16E1 had much heavier firing pins. Great for durability, but it also made it easier to slam fire a rifle.

Load a magazine, charge the handle or drop the bolt, and you get a “bang” instead of a “clang”.

On that note, always be sure to point your weapon in a safe direction.

To be fair, this problem can’t be attributed to any design flaws in the M16/XM16E1. It was a manufacturing issue concerning the sensitivity of the primers.

But it was still a problem.

Parts Breakage

Beyond the malfunctions, the XM16E1 suffered several part breakage problems.

Unfortunately, this isn’t exactly surprising. It’s fairly common for a newly adopted firearm in military service to face parts breakage early on.

The amount of testing a national armory or manufacturer completes can never replicate tens of thousands of grunts firing millions of rounds.

Remember, people: You are the last step in testing and quality control.

That said, a lot of parts in the XM16E1 had a tendency to break. And almost all of them were critical parts.

Bolts would crack, the disconnector on hammer springs would snap off, chambers and bores would corrode, and stocks and grips would crack and break off.

In other words, if the part was necessary for the XM16E1 to function, it would likely break during normal use.

Failure To Feed

This was a far less common problem, but it did occur—and yes, it’s exactly what it sounds like.

The BCG comes forward and, for whatever reason, fails to properly feed a round into the chamber.

However, this is another scenario that can’t be solely attributed to the XM16E1. The aluminum magazines of the time were designed for one-time use—load it, fire it, discard it.

Except the soldiers didn’t—or rather, couldn’t—discard the magazines due to supply issues. Repeatedly using the same magazine resulted in bent feed lips and failures to feed.

What Caused These Problems?!

There are some lesser issues, such as magazine and parts breakage due to quality control failures, but the vast majority of the XM16E1’s problems can be traced to two reasons:

- The U.S. Army willfully used the wrong powder in their ammunition.

- The chamber and bore of the barrels were not chrome plated.

Nearly every problem with the XM16E1 in Vietnam was directly caused by one or both of these issues.

Keep Your Powder Dry… And Use The Right One!

A step back is needed to understand the scope of this issue.

The AR-15 was developed in lockstep with the .223 Remington/5.56x45m cartridge. The history of that round is interesting in and of itself, but we’ll save that for another time.

ArmaLite developed the rifle and helped with the cartridge, but most of the cartridge work was completed by Remington.

For the record, this was done totally outside the military’s purview.

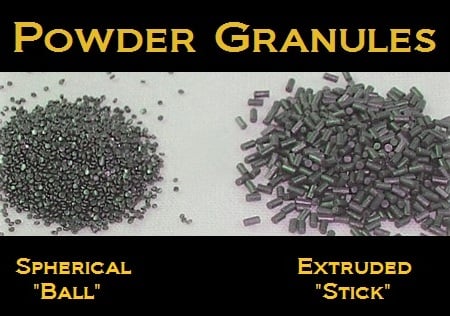

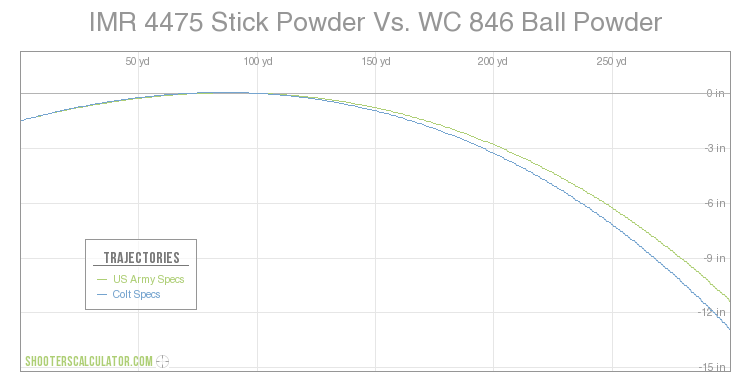

In this new cartridge, they used a specific power, the IMR 4475—an extruded or “stick” powder made by Du Pont and sold to Remington.

However, the U.S. military had a “sole-source” contract (zero chance for corruption there…) for gunpowder with Olin Mathieson, who exclusively manufactured the ball-shaped WC 846 powder for the military.

For simplicity sake, let’s just call them the stick powder and the ball powder.

And just so that it’s easy to remember: stick powder = good, ball powder = bad.

Sticks And Stones And Bullets May Break Your Bones

Gunpowder is gunpowder, right? No, not at all. Different powder burns differently.

Some burns faster, some slower, some are resistant to temperature, and some aren’t. Basically, there’s a lot of science that goes into gunpowder.

Stoner and ArmaLite designed the M16 to be used with stick powder. The rifle was even tuned (size and placement of the gas port, BCG weight, strength of the parts, tension of the buffer spring, etc.) for stick powder.

Ammunition made with the correct stick powder (manufactured by Remington) was utilized by various forces in the early days of Vietnam, including the ARVN, Green Berets, and the 7th Cavalry in the Battle of Ia Drang.

Stick powder worked. But… why did ball powder not work?

Changing Your Powder May Cause Side Effects

There is a lot of science we could talk about, but I’ll keep this simple. The ball powder had a different pressure curve and burn rate, causing deviating pressures in the rifle than what Armalite/Stoner/Colt intended.

This caused a muzzle velocity increase of about 100-150 feet per second and a cycle rate increase of over 200 rounds per minute. That might not sound like much, but it’s the point source of the M16’s greatest problems.

Change one thing, and you change it all.

Increased pressure in the chamber and bore means more pressure eating at the gas port, causing wear over time and even more pressure in the system.

Any increase in pressure in the system, even before the gas port starts to go, raises the energy of the whole system, starting with moving the BCG back faster and with more violence.

Move the BCG faster and harder, and you cause increased wear on critical parts, such as the bolt and disconnector.

Equal and opposite reactions mean that a faster rearward-moving BCG also equals a faster forward-moving BCG, causing more pronounced bolt bounce and granting the free-floating firing pine more inertia.

Raising the muzzle velocity also means that the dwell time is shorter. Dwell time is the amount of time between when the cartridge starts to burn and when the action of the rifle starts to cycle.

Shorter dwell time means that the pressure in the chamber is higher than it was designed for. Higher pressure means the case is harder to extract because it is still being held against the walls of the chamber of the gas pressure.

Combine that with a BCG that is moving faster and more violently, and you have extractors slipping off rims and torn case heads.

Chrome Plating: Not Just Used To Look Awesome

On its own, the change from stick to ball powder would have been a massive and major problem. But it was exacerbated but another issue, corrosion.

In case you didn’t know, Vietnam is mostly jungle and coastline. It’s very pretty when it’s not being burned by Napalm, but it’s also incredibly wet.

Vietnam experiences an average rainfall of 76″ per year, 90% of which drops during a “rainy” season that lasts about 155 days. The average humidity is 78%.

For context, the average humidity of Florida is 74%.

Fun fact: Steel hates water. And barrels are made from steel. I hope you can see where this is going.

Corrosion in the chamber of the XM16E1 caused pitting, and those pits became a critical downfall of the rifle.

A brass cartridge expands in the chamber to create a gas seal; once the pressure drops, the brass contracts and can be extracted from the chamber.

But if the chamber is filled with tiny pits, the brass swells to fill the void and becomes stuck, resulting in slipped extractors and ripped case heads.

In those rifles, it’s a lot harder to get the case out and normally requires the use of a cleaning rod.

Chrome plating is highly corrosion-resistant and three times harder than steel. Applying chromium to an M16 improves the rifle’s longevity from wear and helps protect the gas port from gas erosion.

The U.S. military discovered these advantages when Americans were fighting Japanese soldiers in the jungles of WWII.

For some reason, they forgot by the time Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

Dear Mom, Please Send Me A .22 Caliber Cleaning Kit

If you’ve ever shot a rifle, then you know they get dirty. This is a fundamental fact of firearms, period.

Yet, the U.S. Army blundered again by refusing to issue cleaning kits with the XM16E1. They claimed that the rifle was “self-cleaning” and would not require a cleaning kit.

The official U.S. Army training manual of the time stated: “an occasional cleaning will keep the weapon functioning indefinitely.” Possibly one of the stupidest sentences ever written.

American fighting men in Vietnam quickly discovered that their rifles did, in fact, need cleaning. And since the U.S. Army wasn’t going to provide, they had to turn to the people who could.

Their families back home.

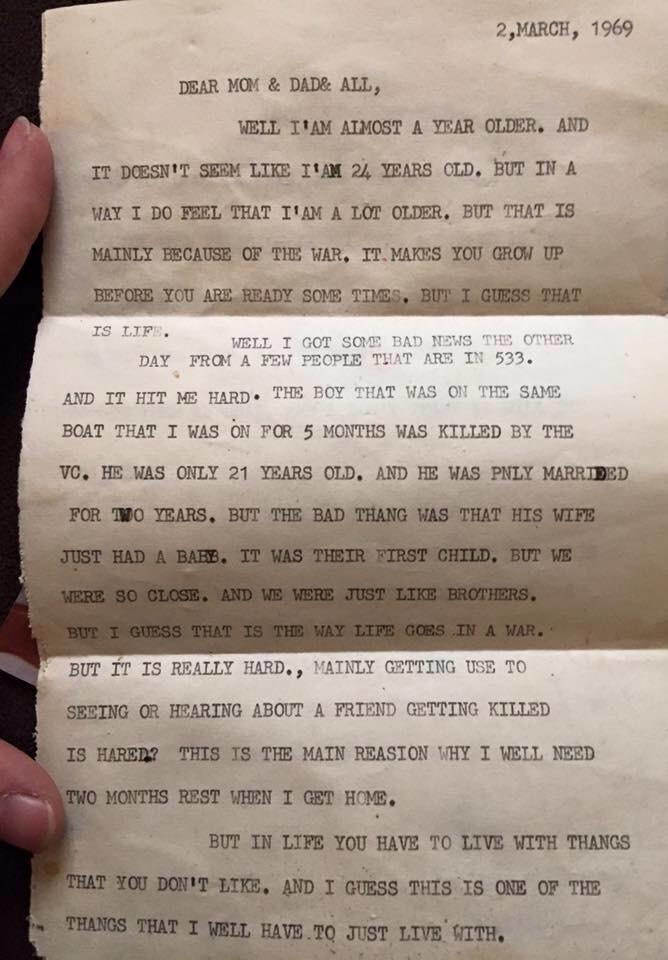

There are hundreds of documented letters from soldiers and Marines in Vietnam writing to their parents, girlfriends, wives, senators, and congressmen back home and begging for basic supplies.

Some of the most common requests? Weapon lubricant, cleaning patches, brushes, picks, and the item most needed of all, bore rods to knock out stuck cases.

One Marine writing his parents explained:

“Out of 40 rounds I’ve fired, my rifle jammed about 10 times. I pack as many grenades as I can plus bayonet and K bar (jungle knife) so I’ll have something to fight with. If you can, please send me a bore rod and a 1 1/4 inch or so paint brush. I need it for my rifles are getting a lot of guys killed because they jam so easily.“

The congressional committee that went to Vietnam to investigate the M16 failures tragically discovered that a Marine was killed in combat because he was the only member of his squad with a cleaning rod.

He died running up and down the line while using his cleaning rod to unjam his fellow Marines’ rifles.

Semper Fi.

How Were These Problems Allowed?!

The deeper we dive into this mess, the angrier you should be.

But the short answer is incompetence, corruption, criminal negligence, and a gross disregard for American lives. And all of it lands squarely at the feet of the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps.

As designed and tested by ArmaLite, Colt, Stoner, and Remington, the M16 is a truly amazing firearm. Reliable, accurate, and deadly.

But the rifle and cartridge they designed were not the same ones fielded by the U.S. Army.

Chrome Is Expensive

Anyone who served in the South Pacific during WWII knew that steel barrels corrode. It was a serious and notorious problem with the M1.

Stoner, ArmaLite, and Colt knew it, too. They all recommended that the chambers and bores of the M16 be chrome plated.

But the U.S. Army refused, citing that it was “unnecessary” and “cost-prohibitive.”

Change The Powder

Up to this point, you might conclude that the problems afflicting the M16 family were due to incompetence or extreme negligence.

But this is where our story takes a turn from stupidity and apathy to clear malicious intent.

In June of 1963, the Army Materiel Command conducted tests at Frankford Arsenal and determined that stick powder was not a viable propellant for the M16.

They also concluded that the Army should instead use the same ball powder American forces had been using since the end of World War 1.

By that point, special forces and ARVN had been using the stick powder for years. But the U.S. Army had spoken.

Why was the stick powder “not viable”?

There is some circular logic in play. Based on the tests at Frankford Arsenal, the Army drew up a technical data package that required the M16 to have a muzzle velocity of 3,250 feet per second and a chamber pressure not exceeding 52,000 PSI.

Based on those specs, they determined that stick powder could not meet the specified requirements. And that part is true.

Your next question should be: Why did they come up with those numbers if they are not remotely what the M16, as designed by Stoner and Colt, could meet, using the ammo they designed?

The official response from the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps during the investigation was:

“In the course of the 5.56mm ammunition program, the Army could have elected to reduce the specified velocity, thus avoiding the necessity of developing new propellants … This would have reduced somewhat the range and effectiveness of the M-16 rifle. Instead, the Army chose to maintain the original [sic] ballistic performance, and utilize propellants which could meet these requirements consistently in mass production.”

In other words, they pulled those numbers out of thin air because that’s what the ball powder produced.

They didn’t care about what was best for the rifle; they choose the powder, tested it, and used the numbers from the ball powder tests to determine what the technical data package should require.

Stick powder was never even in consideration.

After the Army decided what powder they should use, they asked Stoner about his opinion on the data package.

He advised against it and was informed that the decision was already made.

Ignore The Problems

Stoner warned the Army about what would happen with the new data package.

Colt warned the Army that their in-house tests proved the rifles were not as reliable with ball powder.

In November 1965, the same month that the XM16E1 using stick powder would face combat in the Battle of Ia Drang, Colt tested several rifles and concluded that while none of the rifles were likely to malfunction using stick powder, about half were likely to fail using ball powder.

And this testing was completed using clean, maintained, and functional rifles back home in the states. Not the type of weapons being fired by our soldiers.

The report from Colt was sent to the Army and ignored.

In December of the same year, Frankford Arsenal conducted their own test. They found that the M16 with stick powder had 3.2 malfunctions and .75 stoppages per 1,000 rounds.

The same rifles, loaded with the army’s ball powder, faced 18.5 malfunctions and 5.2 stoppages per 1,000 rounds—a failure rate almost six times as high.

Colt Complicit?

In 1965, a full year after tests proved that ball powder could break the M16 rifle, General William Westmoreland, the commanding officer of U.S. Army Vietnam, sent an urgent request for the adoption of the M16 by U.S. forces in Vietnam.

He had seen firsthand how crucial the rifle would be in the dense jungles of Vietnam and how woefully outdated the M14 was.

His request for 100,000 M16s forced Colt into a tight spot.

Per the Army’s acceptance requirements, the M16s produced by Colt could not exceed 850 rounds per minute, a feat that was nearly impossible with ball powder.

Unable to meet these requirements, Colt declared that they were no longer accountable for the M16 passing the Army’s acceptance test and could not guarantee performance results with the ball powder.

The army, in reply, gave Colt permission to test the M16s with whatever ammunition they wished, so long as it passed the requirements.

Colt, having several millions of stick powder ammo in stock, used it to test the rifles and “pass” the requirements. The Army was okay with this, even though the rifles didn’t meet the technical data package specifications when paired with the stick powder.

Colt delivered more than 330,000 rifles under this agreement.

Several years later, the Ichord Committee concluded:

“the rifle project manager, the administrative contracting officer, the members of the Technical Coordinating Committee, and others as high in authority as the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Installations and Logistics knowingly accepted M-16 rifles that would not pass the approved acceptance test.“

Colt knew the M16 couldn’t meet the requirements, as did the U.S. Army. But instead of fixing anything, the military allowed Colt to just fake it.

At this point, nearly all of the ammunition used by American soldiers in Vietnam was the ball powder that everyone knew didn’t work.

The Ichord Committee’s report further concluded:

“The failure on the part of officials with authority in the Army to cause action to be taken to correct the deficiencies of the 5.56mm ammunition borders on criminal negligence.“

Why Did The U.S. Army Engage In Criminal Negligence?

There are few facts to pursue in this case. No one was charged with negligent homicide or treason; no one went to trial.

But there are some educated guesses we can make as to the motive behind all of this.

The role of the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps was to provide the American military with arms. They designed them, tested them, and produced them. And by the 1960s, had done so for almost 150 years.

But what happens when someone from outside of the military does all of the development?

Stoner designed the M16, but Colt owned the rights to produce it. If the military adopted Colt’s rifle, Colt would build it. And they did.

These circumstances left the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps…obsolete. And all of those high-ranking officers were out of a job.

From the start, the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps hated the M16. They ignored it, degraded it, and slandered it. But due to forces outside of their control, they were forced to accept it.

So, the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps “accepted” the M16 on their terms.

Terms that were impossible for the M16 to meet, which they knew from the start. In short, they sabotaged the M16 project.

The M16A1

After years of the XM16E1 getting men killed, the M16A1 was finally adopted in February of 1967 with ten major engineering changes.

Ironically, these changes were not instituted to fix the M16. They just overhauled the design so it would run better with the Army’s ball powder.

By this time, it was too late to go back to using stick powder. DuPont stopped manufacturing the IMR stick powder back in 1964 because the Army refused to adopt it.

The changes between the XM16E1 and the M16A1 include the buffer, bolt hardness, gas tube, finish on the bolt carrier key, bolt catch, flash hider, firing pin retainer, and disconnector.

The manufacturer also added a raised fence around the magazine release to prevent the unintentional dropping of magazines.

And finally, in May of 1967, a chrome-plated chamber was added to the revision list.

However, none of these changes addressed the greatest issue—the ball powder was simply bad. The new improvements increased the M16A1’s reliability and durability but did nothing to solve its failure to extract problem.

It wouldn’t be until 1970 that the ball powder was finally reformulated to be closer to what the stick powder was all along.

The M16/M4 And AR-15 Today

It’s been 50 years since the problems with the M16 were fixed, but the rifle still suffers from a legacy that it never deserved.

The M16 did not fail in Vietnam. On the contrary, even with its problems, it was in every possible way a vastly superior rifle to the M14.

Fault doesn’t rest with the M16, Stoner, or even with Colt. Instead, it lands with the officers in the U.S. Army who not only allowed the problems to occur, but ignored the designers, the men testing the rifle, and everyone in between.

Today, the M16 and M4 are outstandingly reliable rifles, but only because they are allowed to be.

Civilian AR-15s, as long as they are reasonably well made, are hands down the best rifles you can own for self-defense, competition, or bugging out.

It is honestly amazing just how good of a rifle the platform is when there aren’t people actively trying to sabotage it.

Parting Shots

No one was ever truly held accountable for the crimes committed against the soldiers and Marines who served and died in Vietnam due to gross disregard by nameless officers back home.

As you might expect, during the congressional investigation, people kept their mouths shut or “couldn’t recall” reports or incidents. Documents were never turned in or found, likely burned as soon as the subpoenas showed up, and no grand jury was ever convened.

No proof of corruption was found. While the sub-committee asked that Colt’s profits and Olin Mathieson’s “sole-source” contracts be investigated and audited, congress never followed through.

We’ll never know exactly who is to blame. We’ll never know exactly why they chose to let people die rather than adopt a new powder. And the families of the dead will never find the justice they deserve.

If you like reading this kind of deep-dive article, you should take a look at The Modernization & Failed Indigenization of the Indian Army. Let us know if you’re interested in more of these kinds of articles down in the comments!

The post How And Why The M16 Failed In Vietnam (And Is It Reliable Today?) appeared first on Pew Pew Tactical.

guns

via Pew Pew Tactical https://ift.tt/2m7cc0U

September 6, 2020 at 06:28PM