FIRST LOOK: The Performance Center M&P M2.0 Full-Size Pistol

https://ift.tt/2x5SopN

Smith & Wesson’s Performance Center takes some of the company’s most popular production guns and enhances them to produce a line of semi-custom firearms. Sometimes these guns possess additional features and refinements. But they all receive an extra degree of attention not lavished on standard production guns. S&W Performance Center ‘smiths spend extra time mating internals and polishing parts to perfection for smooth and flawless function.

RELATED STORY

Gun Test: Smith & Wesson Performance Center M&P9L Pro Series Core

Performance Center M&P M2.0 Details

Our publisher, Athlon Outdoors, brought in a number of firearms companies to spend time with writers this past October. The Rendezvous was held inn Driggs, Idaho, and Smith & Wesson was one of the companies to attend. Among the new products was a Performance Center Ported M&P9 M2.0 pistol. Matt Spafford, S&W’s Media Manager, took some time to detail me on the new gun.

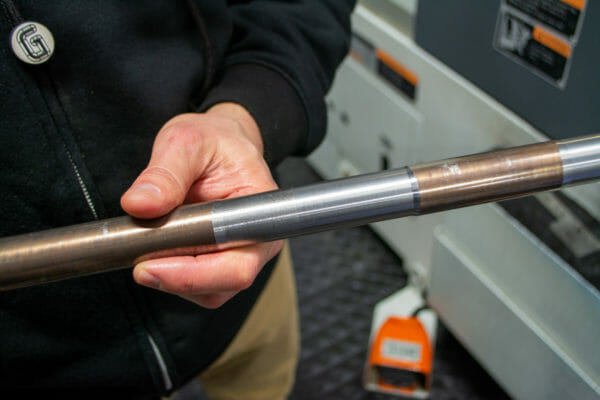

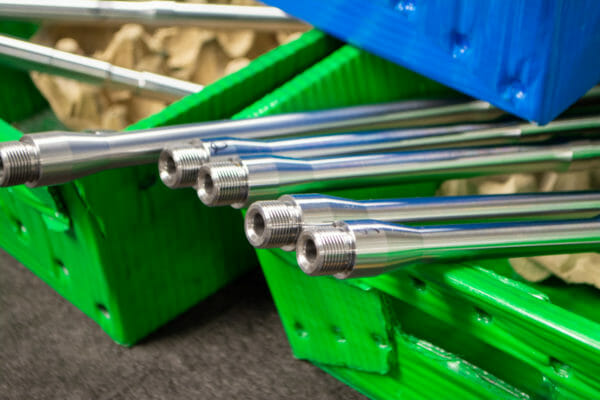

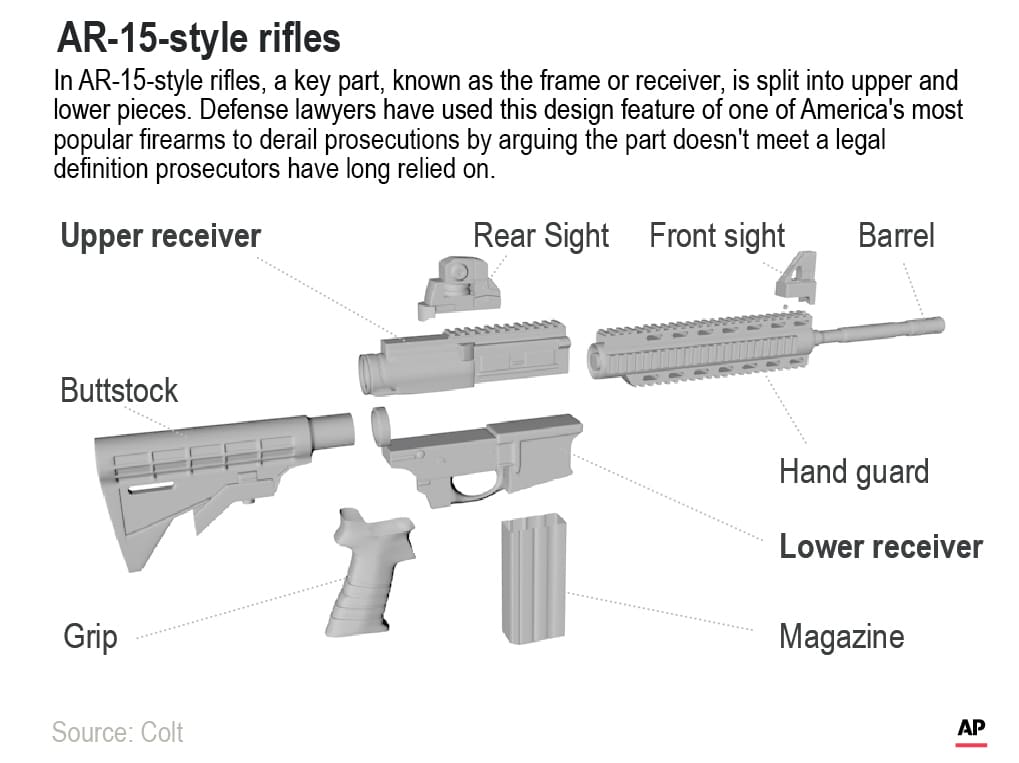

This particular gun features a 5-inch stainless steel and ported barrel and is chambered for 9mm. Because the barrel and slide extend past the end of the M&P9 frame, S&W engineers designed an extended rigid stainless-steel chassis, embedded into the frame’s polymer, to reduce flex and torque. Spafford noted that this gun was the first of the Performance Center offerings to incorporate the new M&P M2.0 upgrades, which include the scale-style cocking serrations, enhanced grip texture, and improved sear geometry, giving the gun a crisper trigger.

Spafford noted the PC craftsmen spend a great deal of time judiciously polishing the sear’s engagement surface. First generation guns possessed a trigger pull around 6.5 pounds, and the 2.0 guns run about 5.5 pounds. Performance Center ‘smiths crafted a trigger pull that broke crisply at 4.5 pounds with a firm and audible reset. Quite frankly, the sample I fired in Idaho had one of the nicest triggers I’ve ever pulled on a striker-fired gun.

Versatile, Full-Size M&P

Building a gun that can fulfill the needs for competition and self-defense can be daunting, but the PC Ported M&P9 M2.0 seems to easily accomplish that mission. Its sights are easily picked up with the front sight, possessing a green fiber-optic rod, while the fully adjustable rear sight has two red fiber-optic rods on either side of the rear notch. Even on a cloudy day the florescent pipettes burned brilliantly, making quick sight acquisition easy.

In keeping with the dual theme of competition and self-defense, the Performance Center ports the barrel and slide in an effort to help minimize muzzle disruption. The Performance Center cuts dual ports on the barrel at the 11 and 1 o’clock positions about 5/8-inch back from the muzzle. In addition to the slide vent ports there are also a number of other slide lightening cuts made to reduce its weight for proper slide velocity. Recoil and muzzle flip of the Ported M&P9 is anything but snappy. In fact, it is a very soft-shooting gun! The combination of the long sight radius, fiber-optic sights, crisp trigger and firm reset made it possible to fire astonishingly fast and accurate double taps. The Performance Center makes guns with competition in mind, designed to shoot fast and stay on target, according to Spafford.

The PC Ported M&P9 M2.0 also possesses a railed dust cover, so a weapon light and or laser can be mounted for low-light defense. It also has an ambidextrous slide lock located on the right side of the frame. S&W ships the pistol with two 17-round magazines as well as a Performance Center cleaning kit. Backed by S&W’s lifetime service policy, the PC Ported M&P9 M2.0 should provide its user with a first-rate competition and defense gun.

For more information, visit smith-wesson.com.

Performance Center M&P M2.0 Specs

- Caliber: 9mm

- Overall Capacity: 17+1

- Barrel: Stainless Steel, 5-inch, Ported

- Action: Semi-Auto, Striker Fired

- Overall Length: 8.5 inches

- Overall Weight: 30 ounces

- Front Sight: Fiber-Optic, Green

- Rear Sight: Fully Adjustable, Fiber-Optic, Red

- Slide: Stainless Steel, 5-inch, Blackened With Armornite

- MSRP: N/A

The post FIRST LOOK: The Performance Center M&P M2.0 Full-Size Pistol appeared first on Tactical Life Gun Magazine: Gun News and Gun Reviews.

guns

via Tactical Life Gun Magazine: Gun News and Gun Reviews https://ift.tt/2i7bVLS

January 15, 2020 at 10:24AM