Years of steadily accumulating dust and grime had taken a toll on King Tut’s tomb, but a recently completed restoration project has revitalized the historic chamber, while making much-needed infrastructure improvements to prevent ongoing decay.

It’s been nearly a century since British archaeologist Howard Carter first peered into the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Since then, the site has attracted millions of visitors, which, while great for the Egyptian economy, has not been so great for the chamber itself. Its majestic wall paintings became dim, drab, scuffed, and scratched from all the moisture and kicked-up dust from the ceaseless train of shuffling tourists.

Determined to not let this World Heritage site go to waste, the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), in cooperation with Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities, embarked on a 10-year project to restore the tomb and introduce much-needed infrastructure improvements. The project, which began in 2009, was completed in the fall of 2018, as reported in a GCI press release.

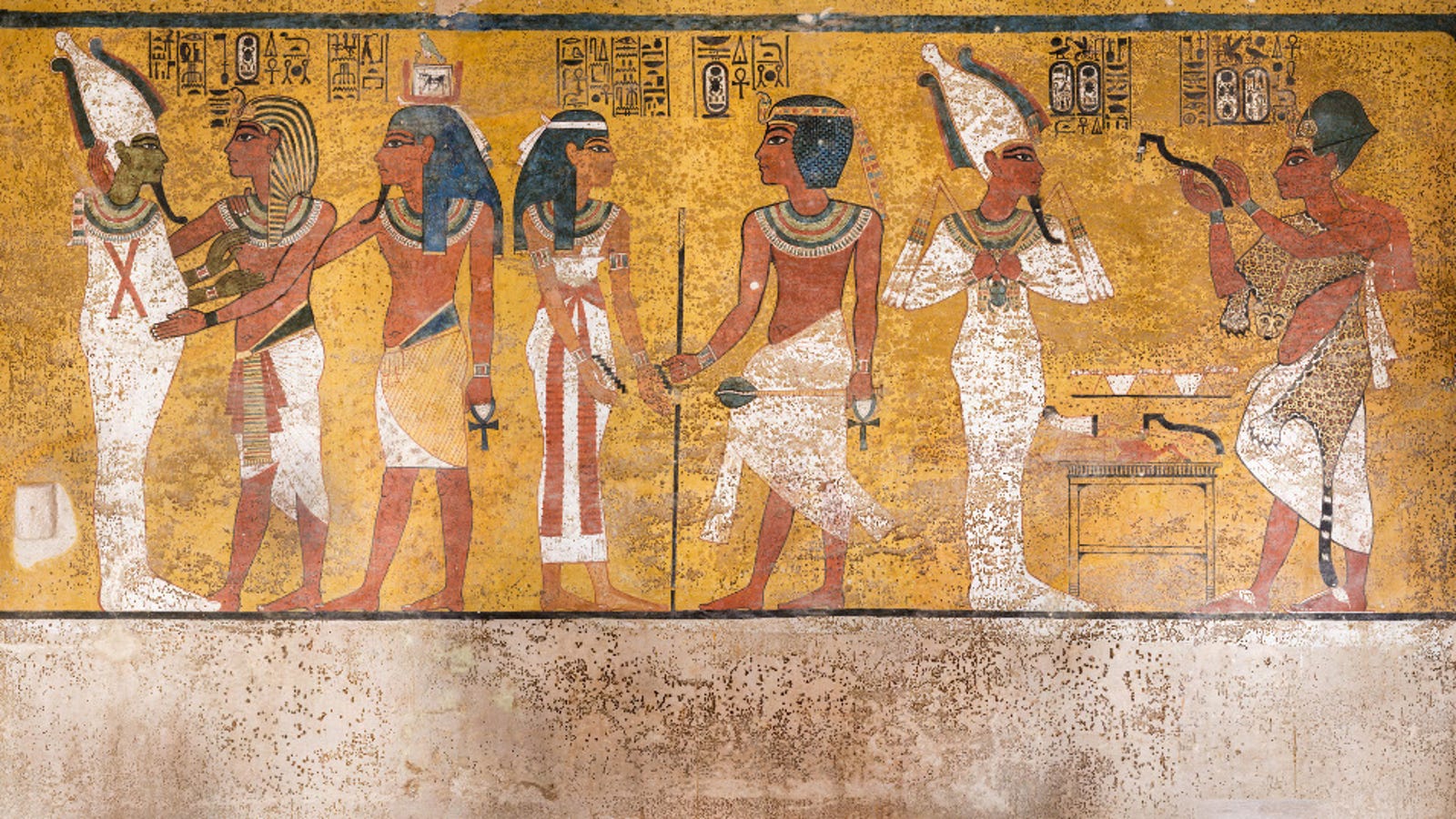

The 3,350-year-old tomb is located in the Valley of Kings near the Egyptian city of Luxor. Rock-cut steps lead down some 40 feet to four chambers, of which only Tut’s burial chamber is adorned with painted walls. Most of the chamber’s relics were removed after its discovery in 1922, but some artifacts remain, including the quartzite sarcophagus and its granite lid, the gilded wooden coffin exterior, and the man himself, whose mummy is on display in an oxygen-free case.

Intense interest in the tomb has caused problems, however. Dust delivered to the tomb by tourists cast a gray veil over the walls. Concerns emerged that increased levels of carbon dioxide and humidity were stimulating microbial growth, including some worrisome brown splotches on the paintings. Some areas of the chamber exhibited scratch and scuff marks caused by tourists and film crews. The microclimate inside the chamber was also unpleasant for the visiting tourists. The tomb was cramped and crowded, poorly lit, and devoid of helpful signage.

The recently completed restoration project addressed all these issues, while also offering a multi-year plan for the ongoing conservation and management of the site. An added benefit of the project was that it resulted in the most “thorough study of the tomb’s condition since Carter’s time,” according to the GCI. The interdisciplinary restoration team was tasked with learning more about the materials used to paint the walls, the microclimate within the chamber, and the apparent microbial growth on the walls. At the same time, the team had to devise strategies for repairing and restoring the artwork and propose infrastructure upgrades to maintain the interior and improve visitor experience.

“As in all of our collaborative projects, the GCI has taken the long view, with the intent to provide sustainable conservation and site management outcomes,” Neville Agnew, senior principal project specialist at GCI, said in a statement. “This involves systematic planning, documentation, scientific investigation, personnel training and a sensitive approach to treatment.”

Careful analysis of the wall paintings showed they were in relatively decent condition, but with some flaking and paint loss. This was on account of the damage inflicted by tourists, but also the result of the materials used by the ancient Egyptians, according to GCI. Conservationists carefully removed dust from the paintings, while also removing protective layers applied during previous treatments.

As for the brown patches, they turned out to be a false alarm. An analysis of photos taken of the chamber after its discovery showed the brown splotches were already there. What’s more, a DNA and chemical analysis confirmed the patches as belonging to an expired fungus that no longer threatens the walls. Unfortunately, the fungus penetrated into the paint itself, and it’s not possible to remove these blemishes without damaging the paintings even further.

Mercifully, barriers now restrict access to the wall paintings. The team also added new walkways, a viewing platform, new signs and lights, and an air filtration system to control humidity, carbon dioxide, and dust.

A cool aspect of this project is that, during the 10 years it took to complete, the tomb remained open to visitors. During that time, the tomb was also made available to scientists, including a team from the Polytechnic University of Turin who in 2018 concluded that no secret chamber exists behind Tut’s tomb.