https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/enemycloset-760×380.jpg

The archived hour-long chat is a must-watch for any long-time Doom fan.

While Doom can sometimes feel like an overnight smash success, the seminal first-person shooter was far from the first game created by id co-founders John Carmack and John Romero. Now, in a rare joint interview that was livestreamed during last weekend’s 30th-anniversary celebration, the pair waxed philosophical about how Doom struck a perfect balance between technology and simplicity that they hadn’t been able to capture previously and have struggled to recapture since.

Carmack said that Doom-precursor Wolfenstein 3D, for instance, "was done under these extreme, extraordinary design constraints" because of the technology available at the time. "There just wasn’t that much we could do."

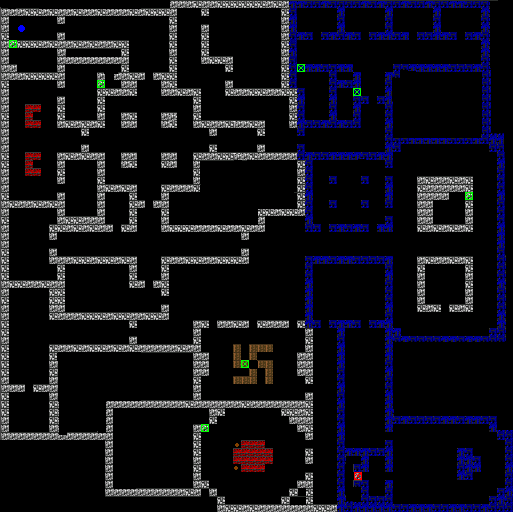

Wolfenstein 3D‘s grid-based mapping led to a lot of boring rectangular rooms connected by long corridors.

One of the biggest constraints in Wolfenstein 3D was a grid-based mapping system that forced walls to be at 90-degree angles, leading to a lot of large, rectangular rooms connected by long corridors. "Making the levels for the original Wolfenstein had to be the most boring level design job ever because it was so simple," Romero said. "Even [2D platformer Commander Keen] was more rewarding to make levels for."

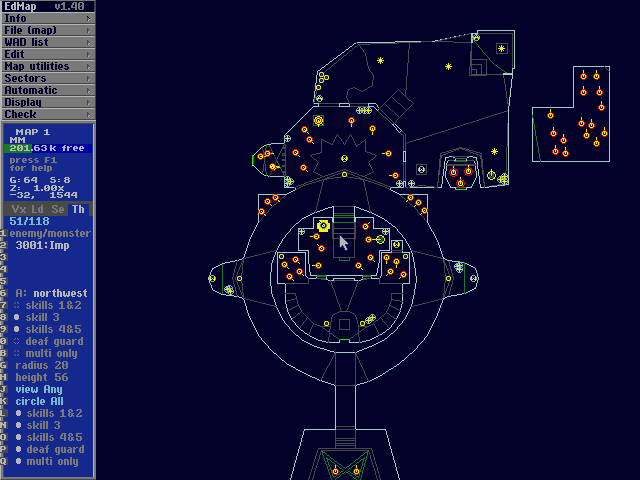

By the time work started on Doom, Carmack said it was obvious that "the next step in graphics was going to be to get away from block levels." The simple addition of angled walls let Doom hit "this really sweet spot," Carmack said, allowing designers to "create an unlimited number of things" while still making sure that "everybody could draw in this 2D view… Lots of people could make levels in that."

Doom‘s support for angled walls and variable heights added a huge amount of design variation while still keeping things relatively simple to edit.

Romero expanded on the idea, saying that working on top of the Doom engine was, at the time, "the easiest way to make something that looks great. If you want to get anything that looks better than this, you’re talking 10 times the work."

Was Quake too complex?

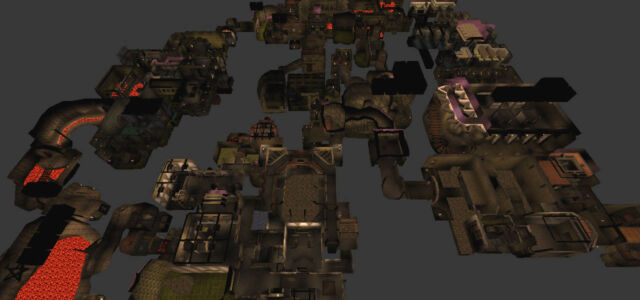

Then came Quake, with a full 3D design that Carmack admitted was "more ambitious" and "did not reach all of its goals." When it came to modding and designing new levels, Carmack lamented how, with Quake, "a lot of potentially great game designers just hit their limit as far as compositional aesthetic in terms of what something is going to look like."

"When you have the ability to do a full six degree-of-freedom modeling, you not only have to be a game designer, you have to be an architect, a modeler working through your composition," Carmack continued. "[Doom] helped you along by keeping you from wasting time doing some crazy things that you would have had to be a master of a different craft to pull off… Going to full 3D made this something that not everybody does on a lark, but something you set out time, almost set a career arc to make mods for newer games."

Enlarge / Quake‘s full 3D maps required much more design skill to build good-looking levels.

Romero reminisced during the chat about "the Everest of Quake" and "the insane amount of technology we took on" during its development. "Even adding QuakeC on top of [a] client/server [architecture] on top of full 3D, it was so much tech. It was a whole new engine, it wasn’t Doom at all. It was all brand new."

Looking back, Carmack allowed that "there’s a couple different steps we could have taken [with Quake], and we probably did not pick the optimal direction, but we kept wanting to make this, just throw everything at it and say, ‘If you can think of something that’s going to be better, we should just strive our hardest to do that.’ When Doom came together, it was just a perfect storm of ‘everything went right.’.. [it was] as close to a perfect game as anything we made."

Ars Technica – All content