https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/math3-760×380.jpg

Enlarge / Math for English Majors talks about numbers as nouns, verbs as calculations, and algebra as grammar.

Ben Orlin

Galileo once famously described the universe as a great book "written in mathematical language and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures." Unfortunately, it’s a language that many people outside of math and science simply do not speak, largely because they are flummoxed and/or intimidated by the sheer density of all that strange symbolic notation.

Math teacher extraordinaire Ben Orlin is here to help with his latest book: Math for English Majors: A Human Take on the Universal Language. And just like Orlin’s previous outings, it’s filled with the author’s trademark bad drawings. Bonus: Orlin created a fun personality quiz, which you can take here to find out your mathematical style.

Orlin’s first book, Math with Bad Drawings, after his blog of the same name, was published in 2018. It included such highlights as placing a discussion of the correlation coefficient and "Anscombe’s Quartet" into the world of Harry Potter and arguing that building the Death Star in the shape of a sphere may not have been the Galactic Empire’s wisest move. We declared it "a great, entertaining read for neophytes and math fans alike, because Orlin excels at finding novel ways to connect the math to real-world problems—or in the case of the Death Star, to problems in fictional worlds."

In 2019, Orlin took on the challenge of conveying the usefulness and beauty of calculus with tall tales, witty asides, and even more bad drawings in Change Is the Only Constant: The Wisdom of Calculus in a Madcap World. That book is a colorful collection of 28 mathematical tales connecting concepts in calculus to art, literature, and all manner of things human beings grapple with on a daily basis.

Orlin’s most recent book was 2022’s Math Games with Bad Drawings—less a book one reads cover to cover and more a chance for readers to browse randomly at their leisure to find the games best suited to their particular tastes and skills, such as Jotto, a logic-oriented word game invented in 1955 that is similar to Wordle. There were five different categories of games: spatial games, number games, combination games, games of risk and reward, and information games. All could be played with just a few common household items: pencil and paper, coins, colored pens, standard dice, Goldfish crackers, paper clips, your hands, and occasionally an Internet connection. (You can try your hand at a game of Quantum Go Fish here.)

Unlike his prior books, where he carefully avoided most mathematical notation, Math for English Majors is designed to teach readers how to read and interpret mathematical symbols, proofs, and mathematical diagrams. His original vision was to write the math-y equivalent to Lynne Truss’ bestselling Eats, Shoots & Leaves. "It’s a very playful book about English punctuation that weaves together fun stories about the common, the semicolon, and the dash," Orlin told Ars. "But I found that math is just a fundamentally different sort of language, and that template didn’t quite work for me."

Some elements of that earlier vision remain: Math for English Majors talks about numbers as nouns, verbs as calculations, and algebra as grammar, highlighting certain idioms ("exponential") and etymologies "squaring") for good measure.

But Orlin’s main objective is to reconcile the expert’s view of math, "where the notation vanishes and you’re just focusing on the ideas that the notation conveys," with the beginner’s experience of math, "where you can’t even access the ideas because there’s this thick wall of symbolism in the way." Math, says Orlin, is both "a collection of beautiful ideas and a language for expressing those ideas." His approach is the opposite of the usual popularizations of math, where ideas are translated into plain English and notation is largely avoided. Here, the notation is the primary focus.

Ars spoke with Orlin to learn more.

Ben Orlin

Ars Technica: People who are not mathematically inclined usually see all those abstract symbols and their eyes glaze over. Let’s talk about the nature of symbols in math and why becoming more familiar with mathematical notation can help non-math people surmount that language barrier.

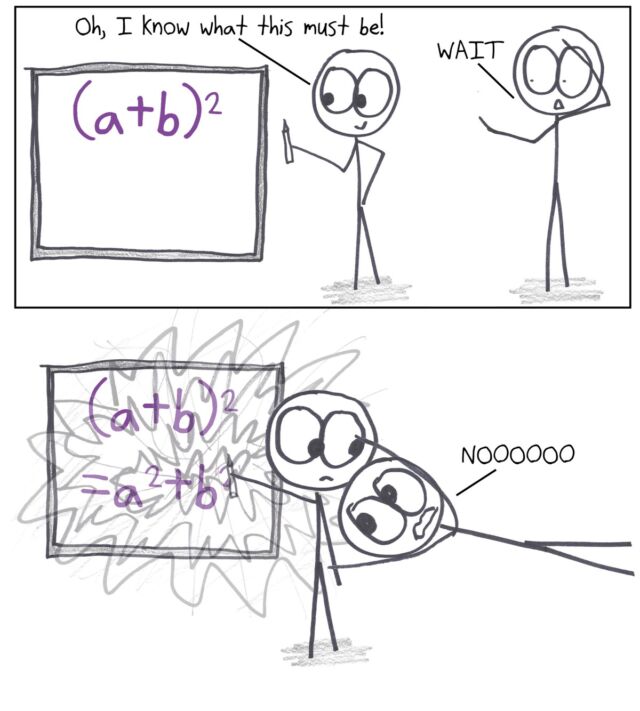

Ben Orlin: It’s tricky. When I first became a teacher, I was mostly trying to push against students who’d only learned symbol manipulation procedures and didn’t have any sense of how to read and access the information behind them. It always mystified me: why do we teach that way? You end up with very bright, clever students, and all we’re giving them is hundreds of hours of practice in symbol manipulation. But what is a quadratic? They can’t really tell you.

One of the things I’ve gradually come to accept is that it’s almost baked into the language that mathematical notation has developed specifically for the purpose of manipulating it without thinking hard about it. If you’ve had the right set of experiences leading into that, that’s very convenient, because it means that when you sit down to solve a problem, you don’t have to solve it like Archimedes with lots of brilliant one-off steps where you just have gorgeous geometric intuition about everything. You can just be like, "Okay, I’m going to crank through the symbol manipulation procedures." So there’s a real power in those procedures. They’re really valuable and important.

But if it’s all you have, then you’re doing a dance where you know the moves, but you’ve never heard the music. You can’t troubleshoot. Sometimes I wish as a teacher, you could just say, "Look, the symbol manipulation procedures are worthless. We can just skip those and focus on the ideas." But they’re tangled up in a much more complex way. So somehow you have to climb in there with the students and move back and forth between the things that are happening on the page and the ideas that are unfolding in some kind of higher space.

That’s the place this book eventually gets to. But I go there gradually, because you need a lot of experience with symbols that make sense to you before you can feel comfortable when you do manipulations on a page.

Ars Technica – All content