https://www.ammoland.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AP5-P-Core-Suppressed-500×282.jpg

1. The Tax Law That Now Finds Itself Without a Tax

In the recent discourse around the potential removal of suppressors and short barrel rifles from the provisions of the National Firearms Act (NFA) and its tax and registration requirements, a point made repeatedly was that if the tax was repealed but the registration stayed, the latter would be illegal as it was only ever justified by the former.

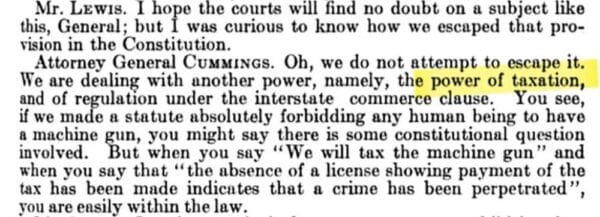

This is indeed correct, as from its inception, the NFA was justified as a tax, with the registration being incidental to that tax and only existing ostensibly to ensure the tax was properly paid for each NFA item sold. Then-Attorney General Cummings was clear about this in his testimony to Congress during the debates over the bill in 1934:

Courts have consistently upheld the NFA, and its registration provision, on the grounds that it was a tax. Some who tried to challenge the law even argued that the tax was a pretext, with the real aim being to unconstitutionally restrict the arms included in the NFA. The Supreme Court rejected this argument in 1937, just a few years after the NFA was first enacted in Sonzinsky v. United States, 300 U.S. 506, 512-514 (1937):

“Petitioner. . .insists that the present levy is not a true tax, but a penalty imposed for the purpose of suppressing traffic in a certain noxious type of firearms, the local regulation of which is reserved to the states because not granted to the national government. . . But a tax is not any the less a tax because it has a regulatory effect. . . Here the annual tax of $200 is productive of some revenue. We are not free to speculate as to the motives which moved Congress to impose it, or as to the extent to which it may operate to restrict the activities taxed. As it is not attended by an offensive regulation, and since it operates as a tax, it is within the national taxing power.”

Ever since then, dozens of rulings have upheld the NFA on those same grounds. For example, in 2018 the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals explained that “the NFA is a valid exercise of Congress’s taxing power, as well as its authority to enact any laws “necessary and proper” to carry out that power.” United States v. Cox, 906 F.3d 1170, 1179 (10th Cir. 2018).

Unfortunately, the Senate Parliamentarian either didn’t grasp this or didn’t care, and struck the repeal of the registration requirement from the “Big Beautiful Bill,” deeming it unrelated to the budget and thus inappropriate for reconciliation. Thus, only the tax was repealed, and so a registration provision that has been justified for over 90 years as necessary only to ensure a tax was paid now finds itself seemingly vulnerable to legal challenge.

The first lawsuit filed against the NFA’s registration requirement unsurprisingly focused on this argument:

“The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which Congress and the President enacted on July 4, 2025, zeroes the manufacture and transfer tax on nearly all NFA-regulated firearms. That means the constitutional foundation on which the NFA rested has dissolved.”

The Plaintiffs in that lawsuit are right to try and exploit this open wound, given courts will no longer be able to lazily uphold the NFA’s provisions on the ground that it is a tax (because there is no longer any tax, at least as to suppressors and short barrel rifles).

But one thing has been strangely missing from this whole discourse: the NFA never had any constitutional foundation, even when it was a tax. Taxes on arms, besides universally applicable sales taxes, are unconstitutional. The NFA should never have been upheld on taxation grounds in the first place, and other taxes such as the 11% assessed under Pittman-Robertson, or California’s similar “sin tax” on guns and ammo, are also unconstitutional.

2. The Bruen Standard, in Brief

To understand why taxes on arms are unconstitutional, a short summary of the Second Amendment analysis is helpful.

In 2022, the Supreme Court unequivocally reaffirmed the original public meaning standard for analyzing Second Amendment challenges set forth in District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008). Applying that test, the Supreme Court found that the Second Amendment protects the right to armed self-defense in public. N.Y. State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n v. Bruen, 597 U.S. 1, 19, 31-33 (2022). The Bruen Court reiterated that courts may not engage in any form of “intermediate scrutiny” or even “strict scrutiny” in Second Amendment cases and unambiguously instructed how a proper Second Amendment analysis is to be conducted by a reviewing court:

“We reiterate that the standard for applying the Second Amendment is as follows: When the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s “unqualified command.”

Moreover, the government cannot simply proffer just any historical law that references firearms. Rather, when challenged laws regulate conduct or circumstances that already existed at the time of the Founding, the absence of widespread historical laws restricting that same conduct or circumstances indicates that the Founders understood the Second Amendment to preclude such regulation. Id. at 27. In contrast, uniquely modern circumstances that did not exist at the time of the Founding call for an analogical analysis, based on the government’s proffered historical record. Id. at 28-29. Outlier statutes do not satisfy the requirement. A law must be a “well-established and representative historical analogue.” Id. at 30.

Courts may not uphold a modern law just because a few similar laws may be found from the past. Id. Doing so “risk[s] endorsing outliers that our ancestors would never have accepted.” Id. (quoting Drummond v. Robinson Township, 9 F.4th 217, 226 (3d Cir. 2021)). In fact, in Bruen the Court acknowledged that two pre-1900 state laws were insufficient to uphold New York’s carry restrictions, despite them being similar to the New York laws. See 597 U.S. at 65 (“the Texas statute, and the rationales set forth in English and Duke, are outliers. In fact, only one other State, West Virginia, adopted a similar public-carry statute before 1900.”).

Finally, as to Bruen’s observation that “unprecedented societal concerns or dramatic technological changes may require a more nuanced approach” (597 U.S. at 27), this case is “fairly straightforward” because there is nothing new about arms, sales of arms, or taxation. In this sort of circumstance, the Supreme Court made clear that the “lack of a distinctly similar historical regulation addressing that problem is relevant evidence that the challenged regulation is inconsistent with the Second Amendment.” Id. (emphasis added).

Further support for this position can be found in the Second Amendment Foundation’s recent victory in a challenge to a California law limiting gun purchases to one per month. There, California argued that the limits were about stopping “trafficking” of arms, and one of the State’s experts stated that during the nineteenth century, “black markets in stolen goods” were a problem and so “Americans were concerned about firearms being sold into the wrong hands.” The panel rejected this argument because “the modern problems that California identifies as justification for its one-gun-a-month law are perhaps different in degree from past problems, but they are not different in kind. Therefore, a nuanced approach is not warranted.” Nguyen v. Bonta, No. 24-2036, 2025 U.S. App. LEXIS 15220, at *18 (9th Cir. June 20, 2025).

The NFA was justified for similar reasons; slowing the trafficking of arms the government considered dangerous. And just like California’s gun rationing law, its tax can only survive if there are “distinctly similar” laws like it in the Founding Era. See also United States v. Rahimi, 602 U.S. 680, 737-38 (2024) (Barrett, J., concurring) (“the history that matters most is the history surrounding the ratification of the text; that backdrop illuminates the meaning of the enacted law. History (or tradition) that long postdates ratification does not serve that function.”).

3. The History of Taxing Arms pre-1900

Now that we know what we are looking for (laws that taxed firearms on a per-gun basis) we can look to see whether any distinctly similar historical laws before 1900 existed in sufficient numerosity to justify modern taxes on firearms, such as the NFA. If any are “distinctly similar” to the modern NFA’s taxation provision, then that provision can be upheld. If not, it is unconstitutional.

The earliest examples were not taxes at all, but rather fines for various violations. For example, a 1762 New York colonial law barred storing more than 28 pounds of gunpowder for those who lived in New York City, and if violated, a fine of Ten Pounds was assessed. To be sure, if someone chose to have more than 28 pounds of gunpowder, they had to store it at a designated “Powder-House,” which required a fee of three shillings per barrel of powder. But that was less of a “tax” and more of a fee for using the powder-house, and in any case, would only apply to those who wanted to have more than 28 pounds of gunpowder. Powder-storage laws in general were not motivated by a desire for taxation or even gun control, but rather fire-prevention; black powder was extremely combustible, and thus a giant safety hazard to the densely packed and mostly wooden cities of the time. See District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 632 (2008) (characterizing colonial powder storage laws as pertaining to fire-safety and not gun control).

Other early examples demonstrate the limits of relying on colonial history. A 1759 New Hampshire law required foreign ships coming into port to pay a tax of two shillings per pound of gun powder, in order to financially support “his Majesty’s fort and fortifications within this province.”

While superficially similar in that this was a tax on a necessary component to firearms – gunpowder – it is not the same as the NFA’s far higher tax on each firearm or suppressor sold, and it only applied to foreign ships. Moreover, with similar laws being sparse or nonexistent, this seems to be an outlier, and “in using pre-ratification history, courts must exercise care to rely only on the history that the Constitution actually incorporated and not on the history that the Constitution left behind.” Rahimi, 602 U.S. at 723 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

In the Nineteenth Century, some laws started to appear that were slightly more similar to the NFA’s taxes. For example, an 1844 Mississippi law taxed Bowie knives at one dollar, and dueling or pocket pistols at two dollars. In modern dollars, that’s about a $43 tax on Bowie knives, and about $86 on pocket or dueling pistols.

But to understand the difference here, it is important to note what was not taxed: the prevailing combat weapons of the time. Bowie knives and pocket pistols were seen as a criminal threat when carried concealed in this era, when those who carried lawfully did so openly. See Nunn v. State, 1 Ga. 243, 251 (1846) (contrasting constitutionally-protected open carry from concealed carry). Some scholars even distinguished the “arms” protected by the Second Amendment from “weapons” which had no such protection. “Arms. . .is used for whatever is intentionally made as an instrument of offence. . .[w]e say firearms, but not fire-weapons; and weapons offensive or defensive, but not arms offensive or defensive.” Joseph Bartlett Burleigh, The American Manual: Containing a Brief Outline of the Origin and Progress of Political Power and the Laws of Nations 31 (1852).

Other similar taxes existed around this late-antebellum time period, like an 1838 law from territorial Florida which taxed dealers (but not buyers) of dirks, pocket pistols, and bowie knives $200 per year. That law also taxed those who publicly carried those specific weapons ten dollars per year. But again, these were not the “weapons of war” of their time, but rather concealable weapons that were used in petty crimes and personal disputes. Moreover, these taxes existed almost exclusively in Southern states and territories, and we have to be careful about relying too heavily on laws from the South given that Bruen looks for a national tradition.

Still, even if these laws were representative of the nation as a whole, there remains the problem that the taxes they enacted did not apply to military arms. A North Carolina law from 1856 makes this especially clear, specifically exempting pistols used for mustering from a $1.25 tax that otherwise applied on all pistols and bowie knives (though the tax only applied if the weapons in question were carried publicly, mere possession was untaxed).

Given these laws were careful not to tax guns like large revolvers, muskets, repeating rifles, and so forth that were used in warfare, how could they be “distinctly similar” to the NFA, which now applies to many arms that are useful in combat roles? For example, the M4 carbine is our military’s most common service rifle, and it has a barrel length of 14.5 inches. In the civilian context (and ignoring that it is also non-transferrable due to being a machine gun) that makes the most common military rifle a short-barreled rifle (“SBR”) subject to the NFA’s tax, which applies to rifles that have barrels under 16 inches in length. (Sig Sauer’s M7 rifle that is set to replace the M4 will be no different, as it has a 13-inch barrel.)

Following the Civil War, many southern territories under reconstruction adopted “Black Codes,” which aimed to keep newly freed former slaves repressed, often with the assistance of the Ku Klux Klan. Strategic disarmament of Black Americans was part of this nefarious project, as even President Grant complained to Congress. See H. Journal, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 716 (1872). It’s no surprise that the Jim Crow era also saw a much more rapid adoption of taxes on certain weapons in the South.

Some of these were barely veiled at all. An 1867 Mississippi law assessed a tax of between five dollars and fifteen dollars on “every gun and pistol,” and if the tax was not paid, the Sheriff was obligated to seize that gun. This seems to be a very close NFA analogue, given it applied to all guns, and the tax was considerable, ranging from $108 to $325 per gun in today’s dollars. The trouble is, the law only applied in Washington County, Mississippi, and not the whole state. According to the 1860 census, Washington County was made up of 92% enslaved people, and even to this day is still over 70% African American. So this law was not some general tax on guns, it was a racist effort to price freedmen out of firearms ownership.

The last large category of taxes related to weapons and arms in the latter parts of the Nineteenth Century are occupational taxes on dealers. These were not assessed on a per-gun basis and are not similar to the NFA’s scheme. For example, an 1885 Kentucky law imposed a tax of fifty dollars on dealers of pistols and bowie knives.

To be sure, some historical taxes existed which arguably may lend support to the practice of including firearms in universally applicable taxes. An 1874 Virginia law included all firearms and other weapons in its listing of taxable personal property, but this was part of a broader tax that encompassed all sorts of personal property including horses, cattle, carriages, books, tools, watches, kitchen furniture, and much more. The tax was 50 cents per every hundred dollars in total value of all this personal property. This is somewhat similar to modern sales taxes, which apply to all goods sold and do not single out firearms for special taxation.

4. Conclusion: Taxes on Common Firearms have no Historical Support and are thus Unconstitutional

While the above was certainly not a comprehensive listing of every historical tax on weapons and arms, it did provide a representative sample of the sorts of pre-1900 laws that existed imposing such taxes. Given Rahimi asks us to look for the “principles that underpin the Nation’s regulatory tradition,” 602 U.S. at 692, there is not much that can be concluded from these laws given the numerous deficiencies they suffer from. They are not a national tradition, but rather a regional one existing primarily in Southern states. They did not usually apply to the prevailing combat arms of the time, but rather to concealable weapons like bowie knives and pocket pistols. And most reprehensibly, they sometimes existed as part of Jim Crow efforts to suppress newly-free Black Americans.

In sum then, while the NFA’s registration provisions are illegal and unconstitutional, we should not ignore that its taxation provisions are historically baseless and violative of the Second Amendment in their own right. The same applies to modern-day federal and state excise taxes, which can likewise point to no distinctly similar historical laws to support their continued existence.

Note: This work is made possible by the Second Amendment Foundation. If you enjoy this article consider becoming a member or donating! Follow us at @2afdn.

About Kostas Moros

Kostas Moros is the Director of Legal Research and Education at the Second Amendment Foundation(SAF). You can find him on X @MorosKostas.

AmmoLand Shooting Sports News