https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/google-chrome-flex-760×380.jpg

Aurich Lawson

October 14, 2025, marks the end of support and security updates for the Home and Pro versions of Windows 10. That means it’s also the end of official guaranteed feature and security updates for Windows PCs that don’t meet Windows 11’s hardware requirements.

Viewed from early 2022, that date is still comfortably far off. Lots of Windows 10 PCs will break over the next 3.5 years, and plenty of people who actually want to upgrade to nicer or faster hardware will have opportunities to do so. But as someone who enjoys repairing, maintaining, and upgrading older hardware to keep it useful, we’ll be peering over the edge of that Windows 10 update cliff before we know it.

The question is: what happens to that hardware when Windows 10 goes away? Running Windows 11 on unsupported hardware is one possible solution, but we have no idea for how long Microsoft will actually allow installing, running, and updating Windows 11 on older PCs; the company could cut off these computers’ security updates tomorrow, or it could allow them to run the new OS indefinitely, and that uncertainty is hard to plan around.

A Linux distribution is another option, particularly the more user-friendly distributions like Ubuntu, Mint, or Elementary OS. But “user-friendly” is relative, and any Linux distribution can have parts that are obtuse and difficult for newcomers to learn. And, let’s face it, if a Linux distribution was going to truly compete with and succeed against Windows on consumer desktops and laptops, it probably would have by now.

Enter ChromeOS Flex, a Google-blessed and Google-supported version of its lightweight Linux operating system that will run on most standard PC hardware. It’s a successor to CloudReady, a ChromiumOS-based product that Google purchased in late 2020 and that we’ve covered since its very early days as a way to make aging PCs into ersatz Chromebooks.

ChromeOS (also Linux-based, but mostly trying to hide it) has managed to find a toehold in the Windows-and-macOS-dominated world of consumer PCs thanks in part to its simplicity, the backing of a large and well-resourced company, and easy-to-use management tools for schools and businesses. And with Flex, Google is offering those organizations the opportunity to switch their Windows laptop fleets to ChromeOS fleets virtually overnight, while also offering users of aging PCs an alternative OS to try.

We’ve downloaded and installed the first developer version of ChromeOS Flex and read through all of its documentation to figure out the kind of hardware it will run on and how it’s different from the CloudReady operating system it’s replacing.

Beware: Beta

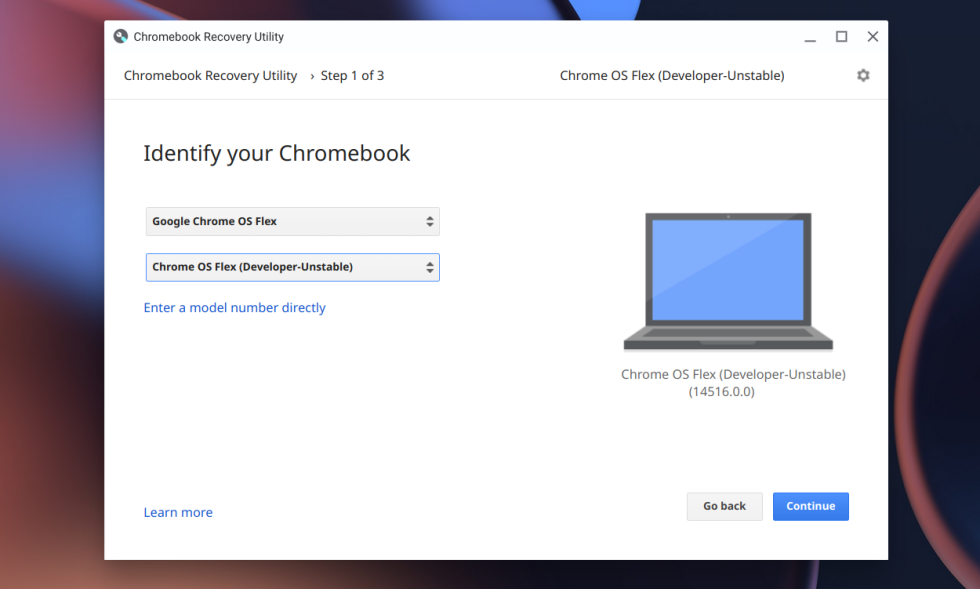

Enlarge / The same tool you use to make ChromeOS recovery media will also make ChromeOS Flex media. And this one USB drive can cover all PCs.

Andrew Cunningham

You’ll find ChromeOS Flex listed among all the “real” Chrome hardware in the official Chromebook Recovery Utility. Select ChromeOS Flex as your device manufacturer and the dev channel build of Flex will show up. There’s no need to download different images for different devices or CPU types. The installation documentation is pretty clear and has lots of details if you need them.

The dev channel build of Flex, based on ChromeOS version 100, is clearly a pretty early version of the operating system. It’s still labeled as “CloudReady” in more than one place, and Google’s list of certified models is filled with reminders to expect minor or major issues. As with CloudReady, it’s possible to run ChromeOS Flex entirely from the USB install drive if you want to try the OS without formatting your internal storage, and that’s what we’d recommend for now.

System requirements and “supported hardware”

At a very bare minimum, ChromeOS Flex doesn’t need much to install and boot, especially compared to Windows 11:

- A 64-bit x86 processor (ARM isn’t supported, nor are 32-bit CPUs)

- 4GB of RAM

- 16GB of internal storage

- USB booting support and full administrator access to the BIOS

Google does note that “components made before 2010 might result in a poor experience.” And if you’re trying to install the OS on an old Intel Atom PC, you might also be out of luck—Intel’s GMA 500, 600, 3600, and 3650 integrated GPUs “do not meet Chrome OS Flex performance standards.” Broadly, though, if a PC runs the 64-bit version of Windows 10 reasonably well, then it should at least boot and run.

To get the best, most Chromebook-like experience—and to be eligible for Google-provided software and hardware support—Google will maintain a list of certified hardware models that it will individually test, troubleshoot, and optimize for. Google’s list of certified models looks pretty similar to Neverware’s list of certified models for CloudReady, which means that it’s heavily weighted in favor of business laptops and desktops. But it includes hardware going all the way back to first-generation Intel Core PCs (and even a handful of Core 2 Duo models), which casts a pretty wide net. Unlike Neverware, Google hasn’t published end-of-support dates for any of these models. But assuming it continues to use Neverware’s timeline, most certified models can expect software support for 13 or 14 years after they were originally introduced.

Google doesn’t require either Secure Boot support or a TPM to install or run ChromeOS Flex, but it recommends that you enable both on PCs that support them. Without the Google-sanctioned security hardware, ChromeOS Flex PCs don’t support ChromeOS’s Verified Boot feature, but enabling Secure Boot “maintain[s] the same boot security as Windows devices.” And having an enabled and working TPM 1.2 or 2.0 module allows for more secure device encryption and support for hardware-backed certificates, among other things. If you’re switching to ChromeOS Flex from Windows, you may need to clear your TPM and then re-enable it so that ChromeOS can use it.

For testing, I used many of the same aging PCs that I used when testing Windows 11 on unsupported hardware. I had the best experience on the newest of those PCs, a 2016-era Dell Latitude 3379 two-in-one with a Core i3-6100U and 8GB of RAM. But Flex also installed and ran OK on an older Windows 7-era HP Pavilion dv5 with a Core i3-540 and 4GB of RAM, albeit with some graphical artifacts and no audio coming out of the speakers (admittedly, this laptop is nowhere on the certified hardware list, though a few other systems of the same vintage are listed).

Hardware limitations

Even assuming that you’re running it on certified hardware, Google has a list of PC features that Flex won’t support and hardware functionality that it isn’t guaranteeing. This includes biometric login devices like fingerprint scanners and IR cameras, SD card readers, display outputs, optical drives, FireWire and Thunderbolt ports (though Thunderbolt 3 and 4 ports should work fine in USB-C mode), and stylus and pen input. External Wi-Fi dongles “often work,” but Google isn’t testing them specifically.

Google also says that boot speed, power-saving features, and battery life might be affected when you install ChromeOS Flex, even on fully certified models. This is par for the course for Linux running on most PCs or Macs, which generally works fine but can reduce battery life because the software hasn’t been optimized for the particular hardware you’re running it on.

Ars Technica